The Three Essential Tools

by Melinda Nielsen

Cosmic education is the plan Dr. Montessori envisioned for the second plane child. However, the implementation of cosmic education requires an adult that is willing to assist the children in their journey to construct themselves. We have the most fabulous job in the world: telling stories about the universe and everything contained within. We are charged with igniting the fire within the child to explore the universe which leads her to discover how everything is connected. In this process the child gains an appreciation for the human beings that came before, their contributions to society and in turn ponders what her cosmic task to society may be.

“We have the most fabulous job in the world: Telling stories about the universe and everything contained within.”

Along with giving the child the invitation to explore the universe there are certain freedoms guaranteed to the child in the Montessori classroom. These freedoms must be balanced with responsibility. Freedom without responsibility leads to chaos and often to traditional manners of teaching.

This is a huge responsibility that rests on our hearts. However, Dr. Montessori did not leave us without a means to accomplish this amazing responsibility. We are armed with the idea of three essential tools to assist the child in his path of accountability and self-construction. These essential tools are the child’s personal work journals, meetings with the child, and having available for the child’s perusal, the societal expectations.

Essential Tool #1: The Journal

The child’s journal is a written account of how the child spends her day. As with all materials in the elementary environment the child must be given a lesson on how to use this tool. The journal is not a place to plan work ahead of time or to write down feelings about a certain assigned topic. It is simply a responsible monitoring of the lessons and freely chosen work that the child participates in daily.

Children do not spontaneously take this task on in a perfect manner. Execution of this tool can be equated to the first great lesson we give the child on the first day of class. Just as the formation of the universe starts out in chaos but ends in a beautiful harmony as the sun smiles upon the earth, the child’s journals take a similar path. Children that are new to the elementary environment or new to Montessori are in need of continual guidance with this responsibility. They arrive at many places in their self-construction. Some are challenged by reading, telling time, and cursive writing; they are not yet accustomed to this ritual.

Ideally, the responsible child will use this tool to make a record of how she spends her time daily. This includes the date, the time an endeavor starts, the name of the piece of work/lesson, and the time it concludes. The child should record how she spends her “down time” and if she leaves the classroom for appointments or “going outs.” Perhaps it may include some well-thought-out illustrations in the margins. The child uses her very best handwriting skills and includes details so that she may recall what she did at a later date. Elementary trainer Phyllis Pottish-Lewis describes it as inspiring the child to “specify, clarify, quantify, and beautify” their journals. This is a phrase that catches the attention of the children and assists in the success of this tool.

Initially, the child’s journal may be a teacher manufactured booklet with a nice colored cover. The journal contains just enough pages for a week at a time. My rationale behind this comes from years of experience. A beautiful bound book, carefully chosen by the child and paid for by the parent, can cause the child to feel like a failure if she is not mentally or physically able to embrace the responsibility. Just imagine the child erasing a mistake made early in the book and the page tearing. As the child continues to use the book, the hole is there to remind her of past mistakes.

When ready, the child can move into a composition style bound book. In the past, these iconic black and white covered books could be decorated by the child as a piece of art. Many times the children would do a painting, drawing, or collage work that could be attached to the cover to personalize it. Currently, these composition books come in many “cute” designs to appeal to the individual taste of each child. As the child gains more control of his hand, gains knowledge of the concept of time and embraces the responsibility of a journal he can move into a bound journal. This journal should be purchased by the child to help him embrace ownership of the responsibility.

As teachers we must embrace Montessori’s advice to follow the child. These first efforts of the child may not reach the ideal form, but the responsibility is still there. The teacher must keep raising the bar until the ideal form is reached. While following the young child, the journals may simply have the date and a rough sense of what was done during the day. To assist the child in this responsibility, perhaps an older child can remind the younger child, assist in spelling and telling time. It would be unrealistic to expect perfect journals from young children, but the expectation of the responsibility needs to be in the culture of the classroom environment.

Many times the children will come up with creative ideas to fulfill this responsibility. It is interesting to see how our wonderful lessons are incorporated into the writings of the children’s journals. For many days after I told the story of pictographs, a child in the community wrote in her journal using pictographs. For example, the sun and earth work became, the (picture of a sun) (plus) (picture of the earth) (picture of child working). In this manner she recorded the work accomplished each day. Oftentimes the illustrations the children use to “beautify” the work take on the theme of the lessons they are working with. A day of mathematics work may be decorated with formulas, geometry with figures, and history with activities of the culture studied. Once the children start working with illumination and calligraphy the journals become works of art. I have even experienced children making notes to themselves about future projects. One particular instance comes to mind. A child entered the upper elementary environment with no experience in Montessori. On the first day of class after he recorded 9:15 am Creation of the Universe 10:05 am, he wrote, This is a big lesson in need of a bigger volcano. I need to make one.

It is the teacher’s responsibility to monitor the child’s path to embracing this responsibility. Teachers must be vigilant when checking on the child’s progress with this tool. One can check in daily in a kind, humorous way just to let the child know it is important. Pay special attention that the child recorded what he did after lunch on the previous day. Perhaps, as the community gathers for lunch or during a time of transition, it is a good time to check on the progress of this tool. Questions can be asked to the community such as:

What was your most interesting work?

What was your most challenging work or, what work did you find challenging?

What did you discover today?

Ask about what they were doing at a certain time.

Ask what work they did with a friend today.

What was the last work done with biology?

Unlike traditional school situations, Montessori children take on this responsibility as a community. After all, in her writings she speaks about recognizing the child as an individual and the children as a group. As the children come together as a community, and the expectation of arriving to the community with their updated journals in hand is part of the culture, they begin to behave as a family would. The children look out for each other and offer assistance to the children that are having difficulty with this responsibility. Recently, in our elementary community, a young child was having a hard time keeping track of his journal. The older members of the community would check in with him as the lunch hour neared. Oftentimes they would assist him in finding his journal. After the first month of school, the children pooled their resources and bought him a journal with a neon cover. He no longer has difficulty meeting his responsibility of arriving to the group with journal in hand.

“Unlike traditional school situations, Montessori children take on this responsibility as a community.”

Above all, set an example by using this tool of responsibility yourself. Purchase a beautiful, bound journal and keep a record in front of the children of the lessons given, meetings with the children, and basically the events of the day. Specify, clarify, quantify, and beautify as a model for the children in the community. As the children travel the journey of this responsibility, before long they will want to share their successes with you. They are the children that approach you with journal hugged to their hearts, ready to share them with you. The glow of self-satisfied responsibility accomplished is written all over their faces.

Essential Tool #2: Societal Expectations

It is the teacher’s responsibility to know what the “outside” culture expects the child to know. This is usually referred to as the public school district’s curriculum, the newly adopted common core curriculum, elements of essential knowledge in private sector settings, etc. Societal expectations do have a place in the Montessori environment but should not take on a life of their own. They need to be thought of as a tool to assist the child in their construction. This tool offers another way for the children to evaluate themselves while they are exploring the whole of cosmic education.

In order to implement this tool successfully, the teacher must have knowledge of the expectations of the local school district, private schools, and charter schools in the area. After all, the teacher must prepare the child for her future school experiences and as a member of her own society. These expectations must be synthesized and possibly rewritten in a form that is accessible to the child. Once completed into this form they can be put into a notebook and placed on the shelf.

This work is offered to the child as any piece of material would be. Although they can be presented to the entire class at one time, a more successful tactic is to present it to small groups yearly. The responsible teacher will make reference to them at the appropriate times to help the child understand his responsibility concerning them. Societal expectations are talked about often in passing and brought out occasionally during meetings with the child.

“Societal expectations do have a place in the Montessori environment but should not take on a life of their own. They need to be thought of as a tool to assist the child in their construction.”

Personally, I like to ask the children how they are doing in a particular area of the environment they have been avoiding. It can be as simple as, “How are you doing with that fraction work society expects you to know by the end of this year?” Walk away… then observe how fast they make a path to where the societal expectations are found in the classroom. Because the classroom is a community, the confident leaders in the class will enable the younger members of the society to evaluate themselves with this tool. If you plant just enough seeds of this responsibility to the right children in the community, this tool will be essentially monitored by the children.

Special care needs to be taken that the societal expectations do not take away from the lessons of cosmic education but that they offer a critical balance to the freedom afforded the child. The bottom line is that having and responsibly using the societal expectations in the classroom provides structure to freedom, offers guidance to explorations, and eases parental anxieties about their child’s education.

Essential Tool #3: The Meeting With the Child

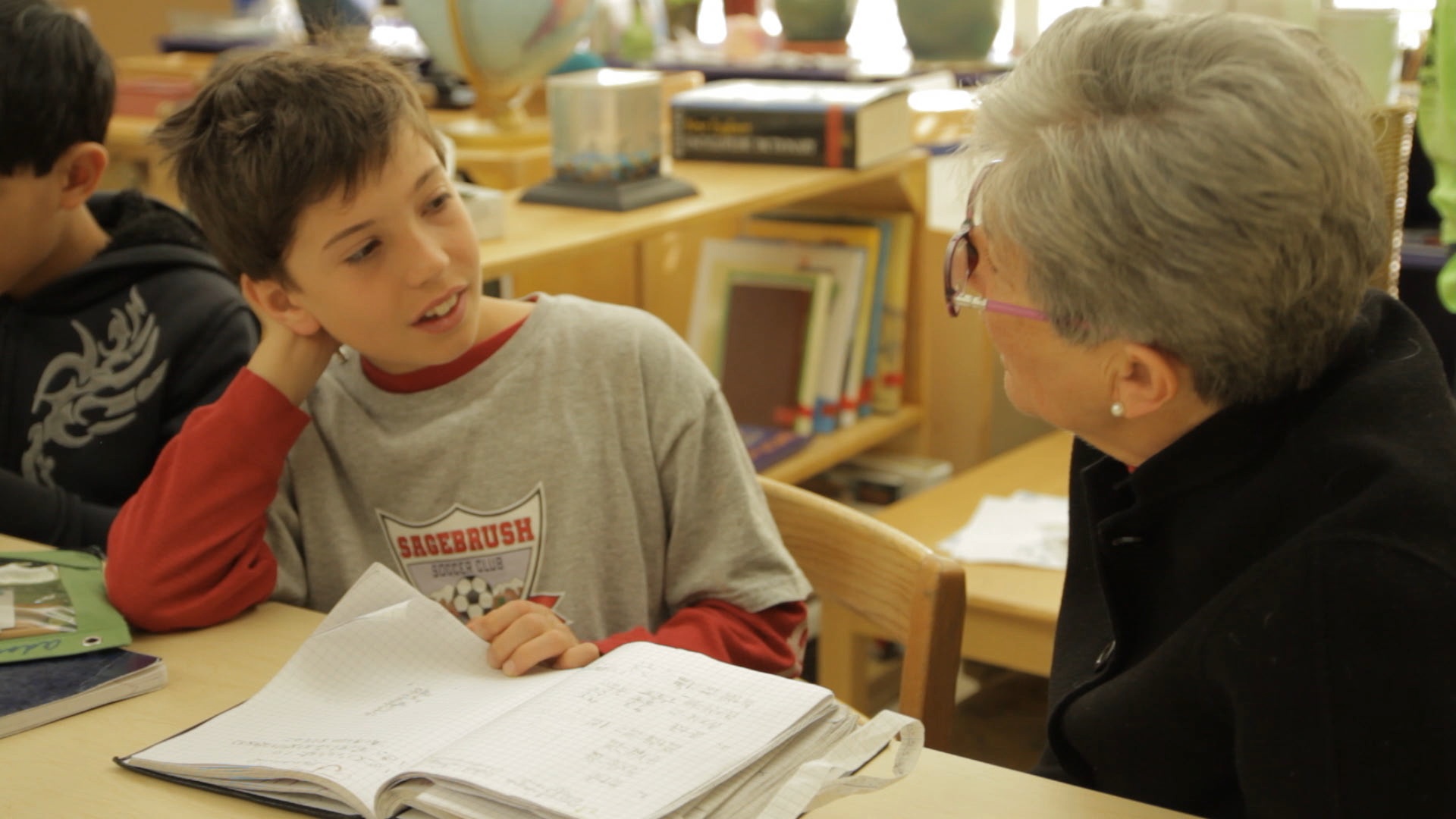

The effort put into assisting the child to keep an accurate record of his endeavors will come to fruition when the teacher meets with the child. This is the time when the child’s journal and work is looked at by the teacher and together they help the child evaluate himself.

Although it is difficult to switch gears from giving the lessons of cosmic education to meeting with children, it is imperative to get into the routine of meetings. A community without the use of this tool is a community with unchecked freedom. Classroom management becomes more difficult, and frustrated teachers may resort to more traditional techniques. Personally, I have two types of meetings with the children: casual and formal. A casual meeting includes a conversation with the child about his progress with his work and possibly, his work in relation to societal expectations. Realistically you may look at his journal but not at the work in his folder. These are the “casual conversations” that occur because the child may be seeking work, a lesson, or taking a break. From experience it is important to personally record these casual meetings in your journal because the children do not seem to recognize them as meetings. You may often hear children saying they never have a meeting but in reality you may have a couple of these casual meetings each day with them.

Sometimes children will meet with you casually to ask for the next lesson in an area of the classroom. An effective approach may be to ask the child what was the last lesson he had in that area. He may need to consult his journal for that answer, which is a good check on how responsible he is with updating his journal. It also plants the idea that he is in charge of his construction. When the title of the next lesson is determined then make a plan with the child when this lesson will occur.

Concerning formal meetings, the child should expect to meet with the teacher on a consistently regular basis such as every two weeks. Older and extremely responsible children may meet less often. We all have children like this in our classrooms. These are the children that you rarely need to meet with but they put in a “special request” for a meeting with you. They are just checking in to let you know how responsible they are and are excited to share their work with you. Perhaps they feel a bit left out because they have the perception that you never meet with them.

This is probably the most difficult tool to implement because the teacher needs to give her full attention to the child she is meeting with. It is helpful to give a lesson to the whole community regarding when the meetings will occur and what is expected of the child at the meeting. The children need to know ahead of time that the expectations are to bring their clean, organized work folders and journals. It may help to post a list of students, sort of like appointments, that are coming to the meetings on that day. This gives them the opportunity to be prepared, and meetings can move along without a lot of downtime.

The agenda for these meetings include:

Taking a close look at the child’s work journal and how he uses his time.

Looking at completed and in-progress endeavors.

Is the child responsible for the freedom given to him?

Is the work of expected quality?

Has the child explored all areas of the environment or just his favorite?

What lessons have been given to the child by the teacher and/or his peers?

Has the child followed up appropriately on the lessons given that are essential to societal expectations?

Has the child made responsible choices?

In the meeting the work is quickly reviewed, always listening to the child’s self-evaluation. The teacher should be prepared to offer loving guidance to enable the child to think of alternate solutions, improvements, and suggestions to be responsible for his education. The skillful teacher may plant the seeds of suggestions but never impose or dictate the end result. Make note of work that does not meet the expectations and kindly let the child know she can do better. Perhaps she was not interested in the work or running out of time to complete it. Listen with empathy but let her know that she is capable of great work. Whatever is discussed during these meetings must be followed up on in the future. If the teacher neglects to follow up, the child does not have a clear responsibility check on her freedoms.

“A teacher draws the best from the children through understanding, through studying their individuality and then putting the child on its own resources, as it were, on its own honor. And believe me, from my own experience of hundreds, I was going to say, thousands of children, I know that they have perhaps a finer sense of honor than you and I have.

The greatest lessons in life if we would but stoop and humble ourselves, we would learn not from grown-up learned men, but from the so-called ignorant children.”

Mahatma Gandhi, 1931 London

In community-wide conversations and in meetings with the children I have found it useful to freely use the terms we find in Montessori’s writings. Recently I overheard an inspiring conversation between an older child and two younger children in our community. The younger children were asking the older child about self-construction. They had talked about it for a bit of time and were confused about what was being constructed. The older child assured the children that it was quite simple: “ It is like putting Lego blocks together. We need certain lessons to help us understand how the world works and to become part of the society of the world. Each lesson you get is like one of those Lego blocks. The great lessons get us thinking about the next lessons we get to explore. Sometimes the lessons are about the same thing just told a little differently or we hear them differently. We need lots of these lessons or Lego blocks to make sure we are strongly constructed. The best thing about going to a Montessori school is that we can choose which part we are constructing first as long as we are responsible with our freedoms. In fact we can do a lot of things if we are responsible.” Currently, I often hear those children say, “I just got a new Lego block for my self-construction.”

Offering the freedom of cosmic education requires a balance of responsibility. The child’s work journals, the societal expectations, and meetings with the child are three powerful tools we as practitioners are armed with to assist the children in their exploration of the universe. The use of the three tools could be thought of as a choreographed dance: the music, dancers, and director work in collaboration to offer a glorious show. Neglect one of them, the dance fails just as cosmic education, in its full glory, cannot be offered without this collaboration.

> BACK TO: Elementary Age Work

© AMI/USA 2014